Tupac and Notorious B.I.G: A Kenyan Millenial’s Perspective

“Why do you even give a fuck about two American rappers who died the year you were born? Si you write a piece on Lil Pump?”

A friend’s little brother, born after 2000, posed this question to me.

When I was a child growing up, Tupac and Notorious BIG were constantly referenced in the Friday Pulse, my older brother and his older friends had near fist fights on who was a better emcee. I’d watch Poetic Justice with my sister and Channel O would bump either ‘Juicy’ or ‘Changes’ on every throwback countdown.

If this is indeed a quarter life crisis- insisting that everything from my childhood has to mean something, let’s start with my brother’s gangsta rap music.

Esketit then.

The word going round when I first heard about this East Coast/West Coast beef was that Biggie killed Tupac and then Tupac’s mom killed Biggie. I think the houseboy told me this version, and then he taught me how to bend my fingers to make the Crips gang sign.

Bloods wanakuchinja kama mbuzi. Crips watakutafuna kama Krackles.

-Edwin the houseboy.

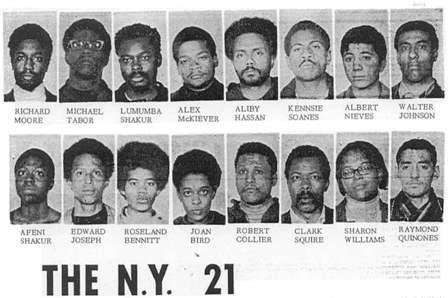

As hard as I know Afeni Shakur was, I mean, she was a black panther – it doesn’t get any more consciously hardcore than that.

But even at 6, that sounded a little far-fetched.

Turns out, no one really knows who the perpetrators in both murders were. Cold cases.

Moreover, turns out their beef was primarily the result of a series of misunderstandings and colliding male egos.

‘Pac and Big met somewhere in ’93 and were boys for the most part- they smoked weed, ogled machine guns and shared meals. Who knows, maybe if they’d hugged it out over Henessy and a bowl of Green, Pac would be on his 12th Studio Album. Biggie would be getting a BET lifetime achievement award, and they’d both be accorded the same reverence as the likes of Dre, Snoop and Nas.

Instead, these raging bulls taunted each other.

After Tupac was shot 5 times at the Quad Recording Studio lobby, Biggie dropped ‘Who Shot Ya?’, poking the injured bear like a bored cackling witch. Now, I’m not gonna speak with certainty as to whether or not Biggie ordered the hit on Pac, but seeing an open window- he couldn’t pass up an opportunity to throw shots.

East Coast, motherfucker (Who shot ya?)

West Coast, motherfuckers West Coast, motherfuckers, hah!

‘Pac took this track as confirmation that Bad Boy were the ones who sent the hitters his way, telling Vibe magazine in one interview that “it came out too fast…”.

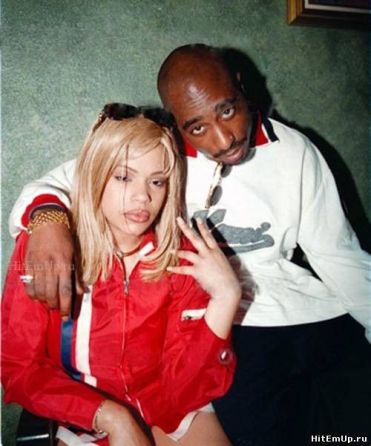

In retaliation, Pac takes a picture with Faith Evans in the club, Big’s girl at the time, and uses that as his below-the-belt ammo, claiming that they smashed.

That’s why I fucked your bitch you fat motherfucker

Let’s put this in context now.

I asked an African American friend who lived in New York and was attending a HBU at the time about this because by virtue of age and race, he was present in the geographical and social context of that whole drama. It didn’t shake his life, not even a jiggle.

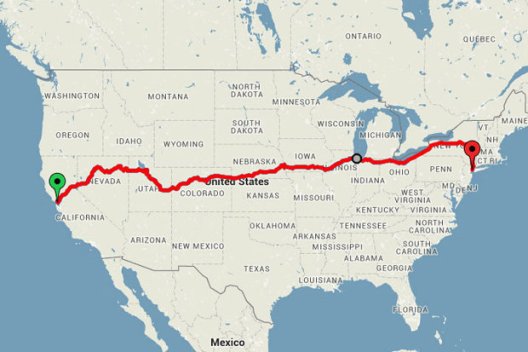

In his words, “The East Coast and West Coast are so far away, you can say ‘Fuck the East Coast’ from L.A and then what? Who’s going to fly from New York to find you and shoot you?”

1995.

Somewhere in Dandora. A bunch of young men are paying close attention. Kalamashaka is comprised of three members: Johnny Vigeti, Kama and Oteraw.

It started out as as imitations of American Mc’s in terms of their rugged flow and punchlinez kibao lyrical style.

The same way hip hop started as a social reflection of what’s happening in the ghetto, Kenyan hip hop became a reflection of life in the slums. English switched out for sheng. Dandora becomes Brooklyn. Police harassment stays the same.

1997.

Rev. Timothy Njoya is wilding on the streets and in church, raging against the Nyayo machine. Moi is president again, going on his 19th year. Political tension sizzles like a wet fish on hot tarmac. K-shaka drops ‘Tafsiri hii’. Kenyan hip hop begins.

Tafsiri hii, maisha kule D ni mazii ninalia nikitumia M.I.C Tafsiri hii, ingawa tuko chini bado tunatumaini.

Sikiza kwa makini

As Tedd Josiah said in the documentary Hip Hop Colony, “the hip hop beats met the Swahili lyrics.”

1999.

Matatu culture is rising strong. Ogopa Deejays are dominating the club scene, dropping hit after party hit and setting the tone for the new millennium.

The street prestige that came from associating with Ogopa Deejays is similar to the pride that came with rolling with either the Death Row or Bad Boy Records. The parties, the liquor, the girls- the staple of both.

A young man from South C wants to be a part of this. He finds himself in a room with Kenya’s reigning producer, Tedd Josiah, this is his chance. Tedd listens to the boy rhyme and then kicks him out of the studio. Who does this kid called E-sir think he is? The Swahili Tupac?

And just like his American predecessors before him, E-sir dies at his prime leaving behind his footprint on Kenyan hip-hop that can never be wiped; that can never fade.

Basically, if it wasn’t for Bad Boy and Death Row we wouldn’t have had Kalamashaka or E-sir, all of whom still stand in history as part of Kenya’s greatest emcees. We wouldn’t have Octopizzo, we wouldn’t have Camp Mulla or Khaligraph and his New York accent.

At least, we wouldn’t have them in the way that we have them/ have had them.

You see, it all comes full circle.

Dunia ni Duara.

It was all a dream.